![]()

“There is a way to do it better – find it…”

— Thomas A. Edison

Modifying Acquisition Practices to Enable Lean-Agile Development and Operations

This is article seven in the SAFe for Government (S4G) series. Click here to view the S4G home page.

The most frequently cited barrier to Lean-Agile and DevOps transformation in government is the legacy acquisition process. Because agencies rarely have all of the personnel, experience, and material needed to create and operate technology-based capabilities, governments rely on industry partners to develop and support mission-enabling solutions. Regulations and guidelines that govern acquisition processes were written to protect citizen interests while creating a fair playing field for businesses competing for contracts.

However, these same guidelines are rooted in legacy acquisition processes that are often too rigid to meet today’s demands for efficiency, innovation, and protection. Instead, they frequently lead to unreasonable delays in contract awards and Big-Up-Front Design (BUFD) processes that force a waterfall development method. Outcomes are often poor. This creates taxpayer dissatisfaction and distrust between contractors and government.

The knowledge pools of Lean-Agile development and DevOps offer an alternative approach. These methods clearly establish the need for a different mindset, as well as new values and principles to govern the new way of working. Trust and transparency among all parties are essential to building the best solution possible within time, cost, and scope constraints. Contractual language that requires big up-front design and full requirements defined early in the cone of uncertainty contradicts this approach.

This article describes how government agencies can expand acquisition practices to include alternative structures, terms, and conditions that enable a Lean-Agile development model while protecting the fiduciary interests of citizens.

Details

Government contracting officers are responsible for ensuring the proper and lawful use of taxpayer money to acquire products and services that enable agency missions. Indeed, in many countries contracting officers can be held personally liable for the misuse or mismanagement of government funds. Naturally, acquisition officials are risk-averse and cautious about making significant changes to the proven practices and contract language that have stood the test of time and legal challenges.

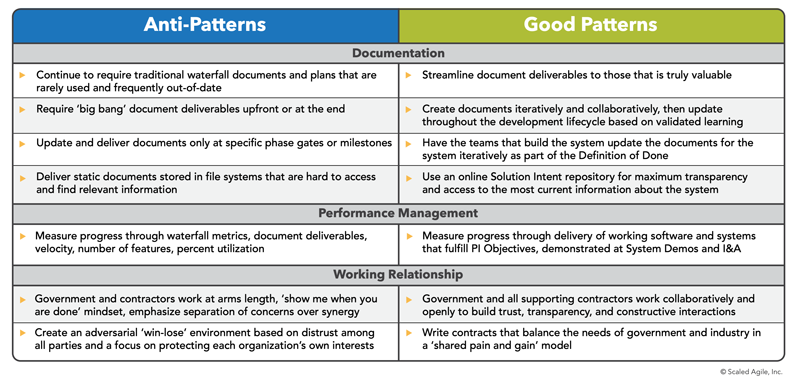

However, the terms and conditions needed for managing a traditional waterfall program compared to Lean-Agile are significantly different. In fact, expecting contractors to use Lean-Agile ways of working governed by waterfall contract language and deliverables has proven to be a formula for failure. Figure 1 below illustrates just a few of the significant contrasts between historical acquisition practices that create anti-patterns for working in a Lean-Agile manner.

The good news is that this is no longer new and uncharted territory in government agencies. Adoption of Lean-Agile and DevOps has grown to the point in the public sector where even the most conservative acquisition officials recognize that these are legitimate process models that require different contracting terms and conditions. Some governments are authoring new guidelines for soliciting, awarding, and managing contracts that support and enable Lean-Agile development (for example the U.S. Department of Defense Software Acquisition Pathway policy). Some even require it.

The sections that follow provide broad guidance for how government organizations can incorporate contracting best practices to support Lean-Agile, DevOps, and their instantiation in SAFe.

Embrace the Goals of an Agile Acquisition Model

First, the shift to Lean-Agile requires more than just changing terminology and activities. Iterative, flow-based development built on the foundations of Lean and Agile demands a shift in mindset, values, and principles, as well as a new set of practices. For example, one of the “big four” values of the Agile Manifesto is “customer collaboration over contract negotiation.” This reflects a vital shift in how both government and industry need to approach the contracting process. To enact this change, however, new values and principles MUST be reflected in the language of the contract.

The goals of a new set of acquisition guidelines to support Lean-Agile contracts should include the following:

- Optimize the economic value for all parties in the short- and long-term

- Provide adaptive responses to new requirements and faster value delivery

- Ensure complete transparency and objective evidence of program performance

- Enable a measured approach to investment that can vary over time and stop when sufficient value has been achieved

- Offer the supplier near-term confidence of funding and sufficient notice when funding winds up, winds down, or stops

- Motivate all parties to build the best solution possible within agreed-to economic boundaries

- Support Lean-Agile principles and practices

Unfortunately, existing boilerplate contract templates frequently promote the opposite of the principles described above. Government and contractors often have a low-trust, win-lose mindset. The language in legacy contracts frequently promotes waterfall processes, enforcing strict adherence to the plan with heavy variance reporting and change control. This limits flexibility and adaptability. In this environment, both sides tend to communicate information on a ‘need to know’ vs. ‘need to share’ basis.

Conversely, the language of a Lean-Agile contract should promote collaboration, transparency, adaptability, and a win-win mindset. Its aim should be to build the best solution possible within the established economic boundaries of time, cost, scope, and quality. Contract language needs to shift from project management, waterfall terminology (integrated master schedules, milestone review, phase gates, EVM, variance reporting, etc.) to Lean-Agile language (vision, roadmaps, backlogs, fast feedback, increments, objective evidence of working systems, etc.).

Develop Government Guidance for Agile Acquisitions

For most government agencies, the historical guidance for acquisition officials is deeply rooted in waterfall past practices. The long-term goal is to modify all policies, regulations, and ultimately statutes to accommodate Lean-Agile models. Change agents should focus on the easiest guidelines to modify first, which are typically agency-level policies. Such guidelines are usually generated on an agency-by-agency basis. Even if the governance office that owns the policy understands the need for an update to support the new way of working, getting the necessary changes approved can be a lengthy yet achievable process. The higher the level of government that owns the policy, the more difficult it will be to effect change. The longest and most challenging changes to make are those that require new laws to be passed by the legislative process. The good news is that in countries like the U.S. and the U.K, laws are starting to be modified to recognize Lean-Agile as a legitimate lifecycle model.

In the meantime, agencies should research the current state of agile contracting guidance and example contracts in their local context. Every country is at different stages in the agile journey. Some, such as the U.S., have made significant progress and are making statutory changes to enable (and in many cases encourage) a Lean-Agile approach. The last section in this article details some of these advances in the U.S. and the resources available to support agile acquisitions.

Agile Solicitation Language to SAFe Taxonomy and Processes

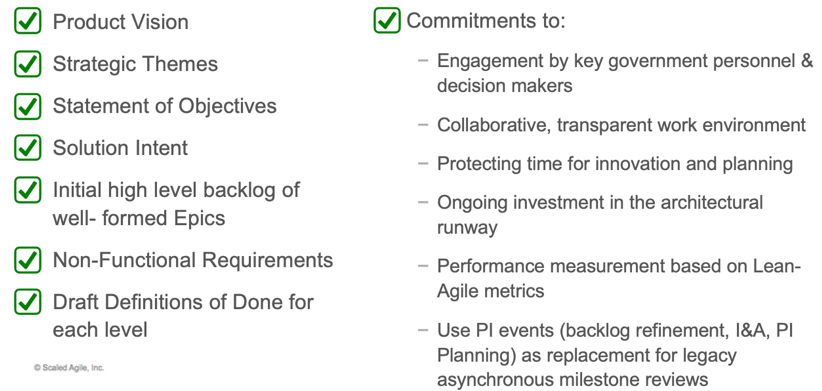

Agencies that have modified their acquisition processes to support Lean-Agile development may also have adopted SAFe as a Lean-Agile and DevOps implementation model. In these cases, acquisition officials can increase alignment with industry partners by creating the expectation in the contract that offerors should be prepared to follow SAFe practices if awarded the work. The graphic in Figure 2 illustrates critical elements to include in the solicitation to create a solid foundation for working in a SAFe environment.

In some cases, agencies can specify that SAFe is the lifecycle model contractors must follow. Other government entities preclude language that prescribes how the vendors will organize and manage their work. But even there, general agile language using a SAFe-like taxonomy can be a big help. When it’s permissible, the more specific the solicitation can be, the greater the communication and alignment will be between the agency and its industry partners.

Access Additional Guidance

In the U.S. there has been substantial progress toward creating resources that provide agencies with the guidance, templates, and tools needed to author contracts that support Lean-Agile development. These are resources developed and published by government agencies, not by industry, for other government organizations to become more open to using these tools.

On the SAFe for Government landing page, there are two areas at the bottom (Resources and Videos) that include entire sections devoted to resources published by the government to support agile acquisitions. At present, most of these resources are designed for use by U.S. agencies, but as the adoption of SAFe grows internationally, this section will be updated with similar country-specific assets. Please check this page frequently and watch for updates in the SAFe Insider and blog page for announcements as new resources are added.

Moving Forward

The next key concept for adopting SAFe in Government is Building in Quality and Compliance.

Next

Learn More

[1] SAFe for Government Landing Page. http://scaledagileframework.com/government/

Last update: 10 February 2021